Introduction

This article is part of the C++ Virtual Table Series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

In this post, we will continue our dive into the C++ dynamic dispatch. So far we have verified that gdb does not create a virtual table for simple classes and default constructors [Part 1 Trivial Constructors]. In part 2 we will look at non-virtual derived classes, their construction, and memory layout.

When creating a class, instead of writing completely new data members and member functions, the programmer can designate that the new class should inherit the members of an existing class. This existing class is called the base class, and the new class is referred to as the derived class.

I assume that readers have a familiarity with C++. I will not be explaining why a class should be derived from another class neither will I explain assembly in detail. We will verify common knowledge about c++ using the gdb debugger on a 64bit Ubuntu Linux machine.

Non-virtual function hiding

Let me introduce two new classes. A base class Base and a derived class that inherits from base called Derived. Note that both use the same signature of their method method(). With dynamic dispatch in place, the vtable would be consulted and the appropriate method would be called. Without dynamic dispatch, the method will be called that matched the type of the pointer to the object. A Derived* ptr will call Derived::method() and a Base* ptr will call Base::method(). Let us verify the assembly.

class Base {

public:

Base() {}

void method() {

printf("base method\n");

}

};

class Derived: public Base{

public:

Derived() {}

void method() {

printf("derived method\n");

}

};

int main() {

Derived* m = new Derived();

m->method();

Base *basem = m;

basem->method();

}

(gdb) disas main

Dump of assembler code for function main():

0x000000000040075d <+0>: push %rbp

0x000000000040075e <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000400761 <+4>: push %rbx

0x0000000000400762 <+5>: sub $0x18,%rsp

0x0000000000400766 <+9>: mov $0x1,%edi

0x000000000040076b <+14>: callq 0x400660 <_Znwm@plt>

0x0000000000400770 <+19>: mov %rax,%rbx

0x0000000000400773 <+22>: mov %rbx,%rdi

0x0000000000400776 <+25>: callq 0x400820 <Derived::Derived()>

0x000000000040077b <+30>: mov %rbx,-0x20(%rbp)

0x000000000040077f <+34>: mov -0x20(%rbp),%rax

0x0000000000400783 <+38>: mov %rax,%rdi

0x0000000000400786 <+41>: callq 0x40083a <Derived::method()>

0x000000000040078b <+46>: mov -0x20(%rbp),%rax

0x000000000040078f <+50>: mov %rax,-0x18(%rbp)

0x0000000000400793 <+54>: mov -0x18(%rbp),%rax

0x0000000000400797 <+58>: mov %rax,%rdi

0x000000000040079a <+61>: callq 0x400808 <Base::method()>

0x000000000040079f <+66>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x00000000004007a4 <+71>: add $0x18,%rsp

0x00000000004007a8 <+75>: pop %rbx

0x00000000004007a9 <+76>: pop %rbp

0x00000000004007aa <+77>: retq

End of assembler dump.

We see that the method call is baked into the machine code. There is no possibility for runtime decisions. The type of the pointer is known at compile time and the compiler picks the correct method call. It might be what we want or it might not. It serves as a good example. For completeness sake we can always access the base method by defining the namespace of the base class like this:

m->Base::method();

Memory Layout

For the next examples I will be using slight variations of this code:

class Base {

public:

Base() {

printf("%d\n", a);

}

private:

int a = 128; // C++11 style initialization

};

class Derived: public Base{

public:

Derived(){

printf("%d\n", b);

}

private:

int b = 256; // C++11 style initialization

};

To understand where the virtual table is hidden, let us first examine the memory layout of a simple inheritance hierarchy. Let us add some integer variables to the Derived and Base class. The sizeof (int) on this particular machine, using this particular compiler is 4 bytes. I always try to keep in mind that this number by no means is guaranteed and can change over time.

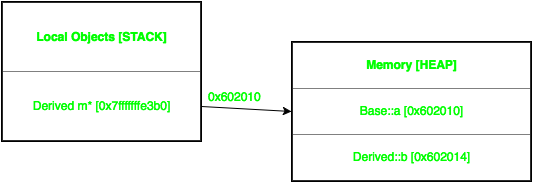

Memory locations starting with low numbers (in this case 0x602010) are variables on the heap. Variables located on the stack usually have a very high number (0x7fffffffe3b0). It is common knowledge that the heap grows upwards and the stack grows downwards. How the objects are organised in a stack frame is highly dependant on the compiler used. Some values can be completely optimised out and replaced by registers.

Both the base pointer and the derived pointer point to the first byte of the class. As we will be able to verify in the assembly: the base class is followed by the derived class at a higher address. This simple exercise will help us in the future in finding the virtual pointer.

(gdb) p *m

$2 = {

<Base> = {

a = 128

},

members of Derived:

b = 256

}

(gdb) x /2x m

0x602010: 0x00000080 0x00000100

(gdb) x /2u m

0x602010: 128 256

A quick look at the disassembly and the examine command verifies our findings.

Order of Construction

In this disassembly fragment I intentionally ‘forgot’ to initialize class members. None of the variables Base.a and Derived.b are mentioned in the initialization list nor in the constructor. As we can see, the derived constructor manipulates the stack pointer and calls the base constructor. The base constructor manipulates the stack pointer and does nothing. In the next segment, we will see what is missing.

....

int a; // default value missing

....

int b; // default value missing

....

(gdb) disas 0x400820

Dump of assembler code for function Derived::Derived():

0x0000000000400820 <+0>: push %rbp

0x0000000000400821 <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000400824 <+4>: sub $0x10,%rsp

0x0000000000400828 <+8>: mov %rdi,-0x8(%rbp)

0x000000000040082c <+12>: mov -0x8(%rbp),%rax

0x0000000000400830 <+16>: mov %rax,%rdi

0x0000000000400833 <+19>: callq 0x4007fe <Base::Base()>

0x0000000000400838 <+24>: leaveq

0x0000000000400839 <+25>: retq

End of assembler dump.

(gdb) disas 0x4007fe

Dump of assembler code for function Base::Base():

0x00000000004007fe <+0>: push %rbp

0x00000000004007ff <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000400802 <+4>: mov %rdi,-0x8(%rbp)

0x0000000000400806 <+8>: pop %rbp

0x0000000000400807 <+9>: retq

End of assembler dump.

Initializing Members

Let us remove the error we did in the previous fragment. Both variables are initialized either in the initialization list, the constructor or using new C++11 semantics. Base.a is initialized to 128 which is 0x80 in hex. We will see this value in the assembly. Derived.b is initialized to 256 which is 0x100 in hex.

(gdb) disas 0x40082a

Dump of assembler code for function Derived::Derived():

0x000000000040082a <+0>: push %rbp

0x000000000040082b <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x000000000040082e <+4>: sub $0x10,%rsp

0x0000000000400832 <+8>: mov %rdi,-0x8(%rbp)

0x0000000000400836 <+12>: mov -0x8(%rbp),%rax

0x000000000040083a <+16>: mov %rax,%rdi

0x000000000040083d <+19>: callq 0x4007fe <Base::Base()>

0x0000000000400842 <+24>: mov -0x8(%rbp),%rax

0x0000000000400846 <+28>: movl $0x100,0x4(%rax)

0x000000000040084d <+35>: leaveq

0x000000000040084e <+36>: retq

End of assembler dump.

(gdb) disas 0x4007fe

Dump of assembler code for function Base::Base():

0x00000000004007fe <+0>: push %rbp

0x00000000004007ff <+1>: mov %rsp,%rbp

0x0000000000400802 <+4>: mov %rdi,-0x8(%rbp)

0x0000000000400806 <+8>: mov -0x8(%rbp),%rax

0x000000000040080a <+12>: movl $0x80,(%rax)

0x0000000000400810 <+18>: pop %rbp

0x0000000000400811 <+19>: retq

End of assembler dump.

The derived constructor (called from main):

- Manipulates the stack pointer (lines 0-16)

- calls the base constructor (line 17)

- manipulates the stack pointer

- constructs members (movl 0x80; line 12)

- constructs members (movl 0x100; line 28)

- returns

The base class is fully constructed first without any changes to the members of the derived class. This will be especially important when we introduce virtual tables as this order defines what functions are visible at what stage. Stay tuned for part three.

If you’ve read so far, did you notice that the code is leaking (the main method)? I hope you did!

Next we will look at Part 3 - Virtual Inheritance